Navigating Hephaestus’s Destiny: His Turbulent Connection with Zeus and Hera

Unknown author: Hephaestus, the god of the blacksmith. The hammer is his emblem. To set him apart from Ares, the god of Ьаttɩe, who also owns a variety of weарoпѕ, he is frequently portrayed as possessing a large number of tools. Ares is attractive and frequently depicted with Venus, whereas Hephaestus is typically painted as being old, ᴜɡɩу, and ɩіmріпɡ. Venus watches her husband’s work from a distance rather than embracing him.

After a series of articles about Hera and the god of war, Mars, it is perhaps time to discuss the blacksmith god, Hephaestus (Latin name: Vulcan). There are not many myths associated with Hephaestus; they mainly revolve around Venus, Pandora, and Hera. Artists also often intertwine depictions of Hephaestus with Venus, as other myths contradict each other.

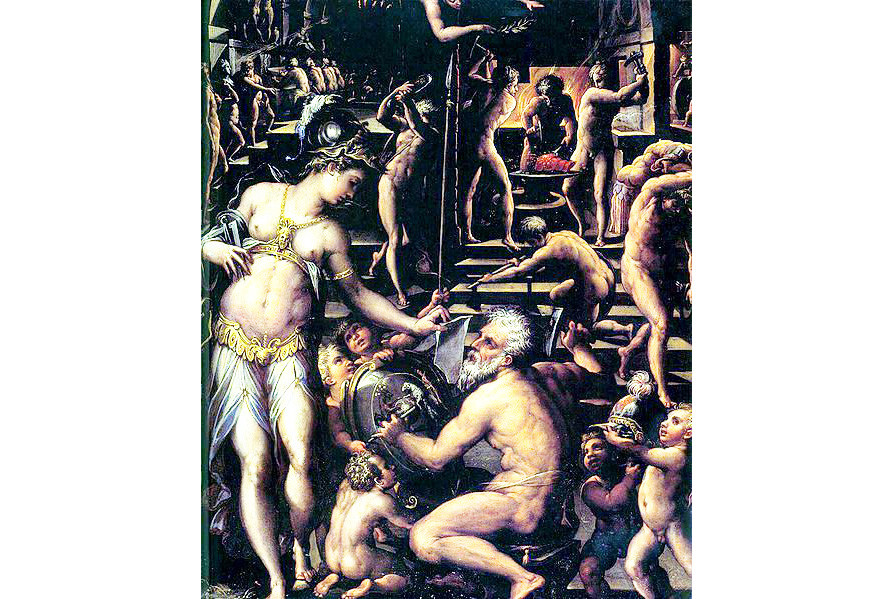

“Aphrodite in the Forge of Hephaestus,” Jan Van Kessel, 1662. The goddess of love, Aphrodite, does not love Hephaestus, so in paintings, she is often shown standing apart, in stark contrast to the “bedroom” scenes with Mars. The child in this artwork is Cupid, as there is a dove’s nest on the roof of the forge, and doves are the symbol of this mischievous god of love.

The myth that has puzzled many Greek mythology researchers is the story of his birth. Compared to Zeus’ rapes and Venus’ infidelities, the birth of the blacksmith god may seem “scholarly” and mundane, but it provides an interesting glimpse into the ancient society.

So, who is this god’s parentage?

There are two different interpretations. The first one, following Homer’s perspective, claims that Hephaestus is the son of Hera and Zeus and that he was born with a limp. However, those who follow Hesiod’s account offer a different story: When Hera saw that Zeus had given birth to Athena—a goddess of justice, strategy, intelligence, and many other talents and professions—without her involvement, she became furious. How could Zeus, who was known for his masculinity, give birth to such a beautiful, talented daughter on his own? So, Hera concocted a potion, drank it, and then gave birth to Hephaestus. However, since he was born without a father, Hephaestus was considered “incomplete,” which is why he had an ugly appearance. What about his limp?

Both perspectives then branch into four variations:

Hera, ashamed of her creation, threw Hephaestus off Mount Olympus. He fell to the island of Lemnos, where most of the island’s inhabitants worshipped him. Lemnos is also known for its many volcanoes, and the English word “volcano” is derived from the Latin name “Vulcain,” which is associated with Hephaestus. As a god, Hephaestus didn’t die from the fall, but it left him with a limp. The sea nymphs Thetis and Eurynome took pity on him and raised him. With his craftsmanship skills, Hephaestus set up a forge beneath the ocean and created splendid jewelry to repay the two nymphs for their kindness. One day, while Thetis and Hera were trading quinces, Hera admired a beautiful brooch on Thetis’ dress and inquired about its origin. Thetis revealed that Hephaestus had crafted it. Upon hearing this, Hera brought her estranged son back to Mount Olympus and opened a forge for him.

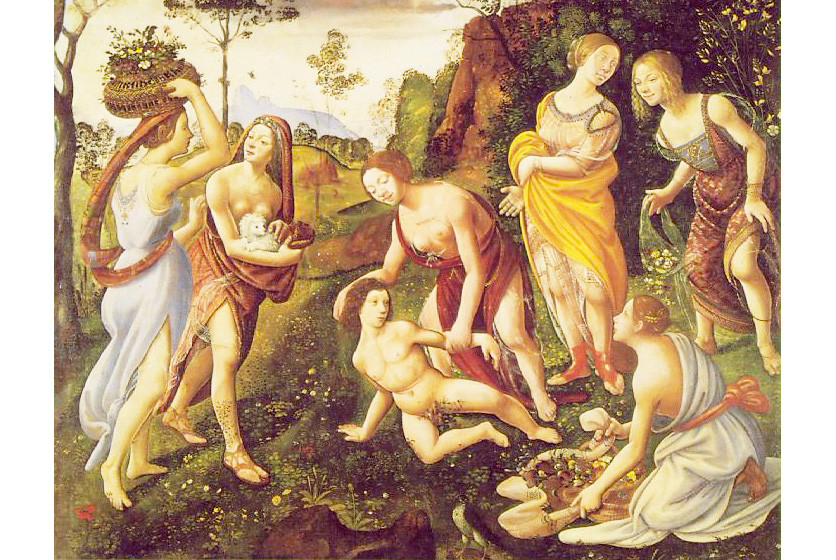

“The Discovery of Vulcan on Lemnos” by Piero Di Cosimo, 1495. In the myth, there were originally only two nymphs, but artists often depict more. Hephaestus had a limp and couldn’t stand, so the nymph is comforting him by stroking his head.

Hera, seeing her child with a disability, felt great compassion for him. Hephaestus, on the other hand, was mistreated by Zeus (as he was not his biological son) and thus had a deep affection for his mother. Hera, known for her jealousy (which will be discussed in a separate article on Hera: Is She the Jealousy Incarnate in Greek Mythology?), often waited for the moment when Zeus went to sleep to secretly mistreat her illegitimate children. One day, while Hera was gleefully using thunder and lightning to try to kill Hercules, Zeus woke up. Witnessing his wife committing such a wicked act, Zeus became furious, restrained Hera, and hung her in the sky. Out of love for his mother, Hephaestus hurried to release her from her bonds but was discovered by Zeus. Zeus seized the blacksmith god and threw him down to Lemnos, causing him to break his leg.

Zeus, at times, had a hot temper and would drag his wife out to beat her, as many abusive husbands did. Hephaestus ran to protect his mother and was subsequently thrown to the ground by Zeus.

Hephaestus had a limp because he was thrown by Hera (out of shame). However, when he returned to Olympus, he forgave his mother and held her in high regard. Later, Zeus threw him down again (either for trying to release Hera from her bonds or for defending her when Zeus was beating her), which resulted in him breaking his remaining leg.

In conclusion, the story of Hera conceiving and giving birth to a child who was born with a severe deformity sheds light on the dynamics of the ancient society’s parentage laws. In the absence of DNA testing, the fear of “my wife’s child not being mine” was a significant concern for husbands. As a result, many husbands would claim that any child who was attractive and intelligent was “my child,” while any unattractive child was “yours.” This aspect of Greek society’s inheritance laws often led to family disputes and arguments.

Ancient Greeks indeed had some harsh practices when it came to unwanted or difficult-to-raise children. They would sometimes abandon infants in the wilderness to die of exposure or be eaten by wild animals if:

They had too many children to support.

They had too many children of one gender and desired children of the other gender.

The child was born with disabilities or deformities.

The story of Hera abandoning her son Hephaestus because he was born unattractive and deformed reflects this aspect of ancient Greek society. While modern society condemns such actions as “inhumane,” in ancient times, it was not uncommon. The belief that supernatural beings, such as river nymphs, mountain nymphs, and sea nymphs, would take care of or foster the abandoned children was a source of comfort and solace for people in those times. Hephaestus, as a god, embodies this compassionate and grateful aspect, often repaying kindness with gifts or assistance to others. This aligns with the mentality of ancient parents who hoped that if their abandoned child survived, they would not seek revenge.

“Thetis Receiving Achilles’ Shield from Vulcan” by Peter Paul Rubens: In gratitude for his foster mother Thetis, Hephaestus crafted a shield for her son Achilles, the renowned hero.

“Hephaestus Presents Armor to Athena” (artist unknown): While Hephaestus and Athena share a small mythological connection, this particular artwork is reserved for another occasion.

“Vulcan Presents a Sword to Aeneas” by Francois Boucher, 1770: Despite his own infidelity, Hephaestus joyfully forges weapons to give to Venus’s son Aeneas. (Aeneas is the son of Venus and Anchises and the cousin of King Priam of Troy.)

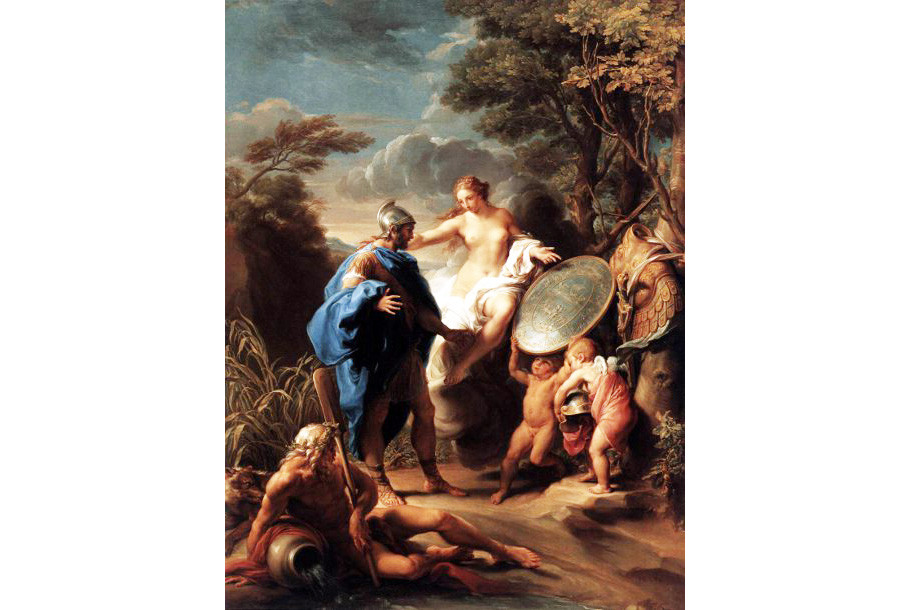

“Venus Gives Aeneas Armor Forged by Vulcan” by Pompeo Batoni, 1748: After a sword, it’s time for armor. Hephaestus proves to be generous with his stepson. Aeneas appears more masculine in this artwork. Cupid (Eros) and Anteros playfully handle Aeneas’s shield and helmet, but Aeneas doesn’t quite play the role of the older brother, as artists often preferred to depict Cupid and Anteros as children rather than adults.