According to Ancient Egyptian legends, the Land of Punt was a mysterious kingdom covered in tropical vegetation, inhabited by exotic animals and rich in treasures, including gold, gemstones, frankincense and myrrh. Modern archaeological evidence suggests that Punt was more than just a legend, but for over 150 years, Punt has been a geographic mystery as nobody could pinpoint its exact location.

In 1858, French archaeologist Auguste Ferdinand François Mariette interpreted a stone relief discovered in the temple of Deir el-Bahari, the mortuary temple build for the famous Queen Hatshepsut, as a realistic depiction of an expedition by ship to the remote Land of Punt. Based on the display of exotic animals and plants, like leopards, apes, giraffes and myrrh trees, some researchers argued that Punt was located somewhere in East Africa or maybe even on the Arabian Peninsula.

The Egyptians first began to travel to Punt about 4500 years ago and continued to do so for more than 1000 years. But although written records and artworks list the many products the Egyptians brought back from Punt – precious resins, metals like gold, silver and electrum, tropical wood, exotic plants and even living animals – scientists have found little hard evidence of these goods in the archaeological record.

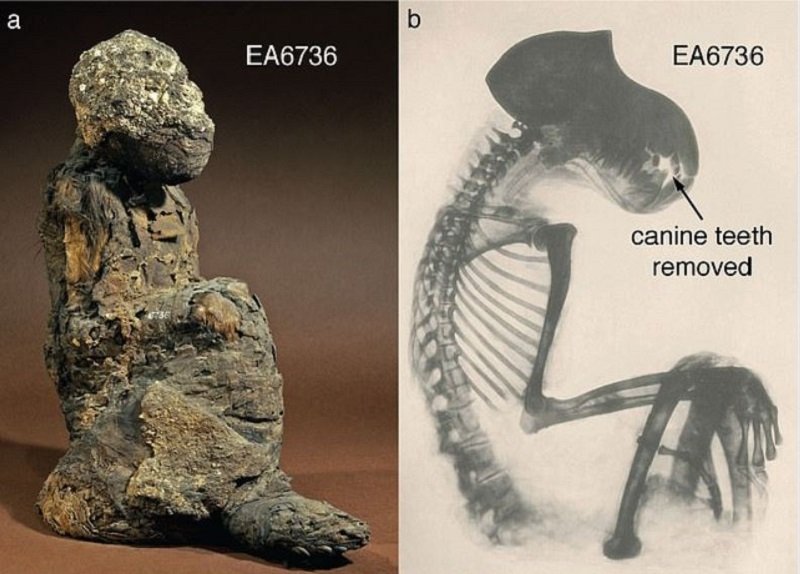

In a 2020 study Nathaniel Dominy, a primatologist at Dartmouth College, and colleagues analyzed chemical traces of a baboon skull hosted in the collection of the British Museum, providing direct evidence that the living animal was brought back to Egypt from Punt.

The remains belong to a hamadryas baboon discovered by 19th-century archaeologists in the ancient Egyptian city of Thebes. This primate is not native to Egypt, but based on the Deir el-Bahari relief, showing baboons climbing around on the returning ship, this species actually lived in Punt. The hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas) is a species of baboon native to the Horn of Africa and the southwestern tip of the Arabian Peninsula.

The researchers studied chemical isotopes in the baboon’s tooth enamel for clues to the animal’s birthplace. The soil and water in a region have a distinctive ratio of strontium, hydrogen and oxygen isotopes, depending on the underlying geology. By drinking water from springs and feeding on plants growing there, animals will accumulate those isotopes in their bones and teeth. Teeth form in the first years of an animal’s life and the isotopic signature of the tooth enamel remains unchanged even if the animal later moves to a foreign land.

The strontium ratio in the tooth enamel confirmed that the baboon found in ancient Thebes had not been born in Egypt. Instead, an analysis of strontium ratios in 31 modern baboons from across East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula suggests the animal was born in an area stretching across modern-day Eritrea, Ethiopia, and northwest Somalia.

That’s where most archaeologists think Punt was located and thus implies the baboon is the first known Puntite treasure, Dominy says.